By Jordan P. Ross

Winemakers agree that Pinot Noir is the most challenging wine to make. Many wine drinkers believe that when Pinot Noir is good, there is no greater pleasure in all of wine. The problem is that unlike Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay, which grow well in France, Australia, Chile, Argentina, Pinot Noir is finicky; it needs specific growing conditions. If you plant Pinot Noir on the wrong site, you end up with poor color, vegetative flavors and no texture. It’s not necessarily true that Pinot Noir is harder to grow, it’s just more site specific.

And even where Pinot thrives such as in Burgundy, Oregon and California’s central and north coasts, there are still hazards. If a wine is hurt by filtration, Pinot Noir will be hurt the most, it oxidizes the fastest, suffers the most from overcropping and in bad vintages will make the most undrinkable wines. It’s more labor intensive and therefore cannot be made in quantity. As such, there is never a lot of good Pinot made and it’s always expensive.

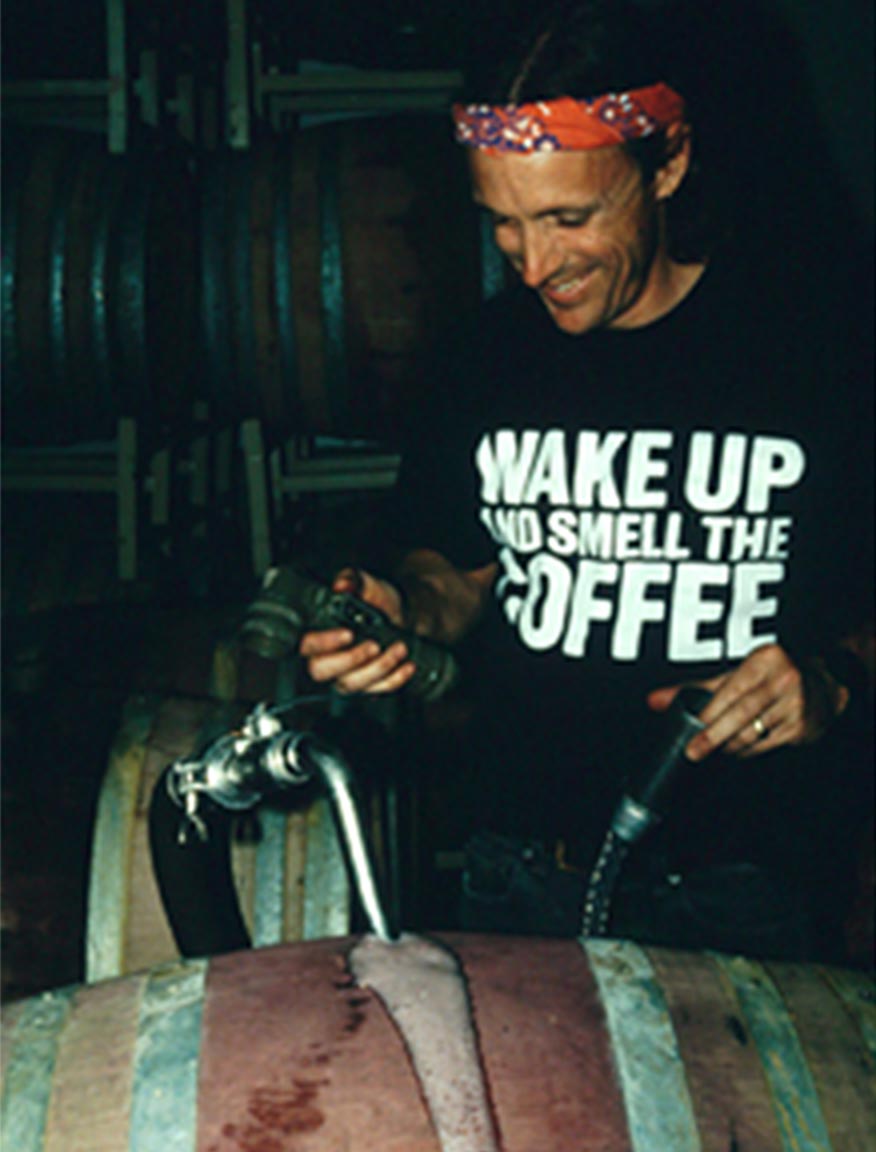

After 19 years making Pinot Noir at Acacia Winery in Carneros, few winemakers have the experience with this fastidiuos grape variety that Larry Brooks has. He briefly experimented with corporate life at Acacia’s parent company, Chalone. During this three year interlude, Larry founded Echelon Winery and managed all of Chalone's wineries and vineyards. Recently, Larry has run a consulting practice out of a cozy office in downtown Napa, while he and Acacia founder Mike Richmond have been slowly growing Amethyst, their Italian varietal winery. In 2000, Larry and a group of investors founded Campion, to produce Pinot Noir from several distinct appellations in California.

Brooks is thoughtful and articulate as well as refreshingly honest, irreverent and outspoken. As one the early and successful producers of single vineyard Pinot Noir, his insights into what many consider the Holy Grail of wines are worthwhile reading.

ROSS: What is Pinot Noir like from a winemaker’s perspective?

Pinot Noir shows the hand or the desire of the winemaker. If he is competent and knows what he’s doing, Pinot lets him. Pinot Noir can be such a wide range of wines, it really forces the winemaker to pick his style. The choices you make—thinning, leafing, ripening, your extraction techniques, how much oak you use—really show with Pinot Noir. That’s why you don’t taste terroir so well in Cabernet, it’s such a dense wine, you can’t see through the wine to get at the terroir. Pinot is more like a white wine, it can be light enough to show off style and terroir.

ROSS: Contrast the enjoyment of Pinot Noir with Cabernet and Chardonnay.

A lot of top Cabs, Zins and powerful Chardonnays, you’re forced to accept them. You don’t have to bring anything to it, they’re going to bring everything to you. You’re going to be forced to have a feeling about them. But really fine Pinot Noir, because it is a combination of complexity and subtlety—you’re seduced or lead to what the wine is, in fact you can miss it. That’s why people who haven’t had the time or experience—and good Pinot Noir is very expensive so it’s not an easy wine to study—tend to go for the obvious. That’s why people love Williams Selyem, they can understand it—it’s black, it’s sweet, it’s oaky. That’s not Pinot Noir, I don’t think.

ROSS: With Pinot Noir, how do you rate quality?

Pinot Noir is different than all other red wines. It’s the only varietal I know where there is such a wide a range of accepted styles. How can you compare something that is light, delicate and perfumed with something that is deep and dark approaching Zinfandel? When people say ‘Oh, I love Pinot Noir’, I always want to say ‘yeah, but what Pinot Noir?’ Do you like it smoky and animally or perfumed and delicate?

ROSS: It seems the ‘clunkers’ are not rejected by the market, they continue to sell.

Because there isn’t any consensus as to what makes a great Pinot Noir. Even among the producers themselves—interesting to think about.

ROSS: That’s interesting. So you’ve sat with winemakers and…had deep disagreements about whether a wine was a good Pinot Noir.

ROSS: When it comes to Burgundian wines in America, Chardonnay is more successful than Pinot Noir. Why?

The best Chardonnay doesn’t even approach the top, middle Pinot Noir in my estimation. The fact that somehow people think white Burgundy is better than red Burgundy, I just don’t think they’re paying attention, their palates are broken. Red Burgundy is so much more intriguing, more complex, long-lived, dies more gracefully than any other wine. I don’t see that in any other wines, maybe some parts of the Rhone like Chateauneuf du Pape; Pinot Noir and Grenache have a lot in common.

ROSS: Compare Pinot Noir to Zinfandel, which also comes in a wide variety of styles, from light and fruity to late harvest.

Zin, even at its best, isn’t Pinot Noir. It’s not a classic variety, it’s not as complex or interesting.

ROSS: It sounds like Pinot Noir is your favorite wine.

After 20 years of playing with it I am still deeply conflicted about Pinot Noir. It’s still the least reliable from a quality point of view. It’s always expensive. I’m constantly running into quite expensive wines from Burgundy, Oregon and California that are frankly disappointing. And I forgive it because I love Pinot best. But at the table, sitting down with twelve wines and ranking them and doing all the secondary chemistry and all that crap, let’s just talk about pouring yourself out a glass of Pinot Noir and thinking, ‘hey, I can drink this whole bottle, no problem. Let’s go get another one so you can have some too.’

ROSS: How is the Pinot Noir drinker different?

One of the things that drives connoisseurship is the idea of variance and complexity and a certain level of frustration. The reason people are collectors and connoisseurs is because they like having a hard time finding stuff and with Pinot Noir you have the hardest time finding top quality. It seems that the more Pinot Noir you drink, the more subtle expressions of it you like. And it’s the reason that in the most experienced Pinot Noir areas, winemakers are very cautious about the amount of new oak they use. I just went to a Pinot Noir symposium at Davis and 90% of the Burgundy producers use no more than 15%-20% new wood. Otherwise, the oak dominates it and you ruin the wine.

ROSS: What do you like?

Something perfumed and racy. You can do it in any number of places. The places that I’ve tasted it done is in the Carneros and Anderson Valley—areas where you’re barely ripening so there is an element of floral and herbal quality that comes from some percentage of underipe grapes. I tasted the ’96 Navarro Methode Ancienne and it was just as much as you could ask for. I’m a huge believer that you need humidity or non-arid conditions to grow Pinot Noir. The coolness helps but one of the reasons that the best Pinots in California are clustered near the coast is the humidity more than the absolute low temperature.

ROSS: What about the new Pinot Noir plantings on the Sonoma Coast?

I had two Hirsh Vineyard Pinots recently. One by Littorai was a really nice wine, a deft expression of Pinot Noir. The other I thought was horrible. I don’t think it was fruit-based, I think it was ripening-based. One was complex and subtle the other was like being hit over the head with a lead pipe.

ROSS: As former winemaker for Acacia and then Chalone Wine Group’s Pinot Noir wineries, you have statewide experience. What appellation produces the most interesting or intensely flavored Pinot Noir?

Burgundy, without a doubt.

ROSS: How about in California?

Depends on what you like. Some of the riper cherry, plum character that is part of the Russian River might be more universally appealing then the lighter, red berry that you tend to get in Carneros. I love Carneros the best. I spent 20 years there. If you spend a long time working in any one area, you know so much about it you lose your objectivity—you have to. It’s like your mother’s cooking—you may eat at a three star restaurant, but you still love your Mom’s cooking.