Anyone who has tasted a great old vintage will testify to the emotionally charged experience it can be. Wine is a link to the natural world and an old vintage itself a link to a time and events long past. The first whiff of the complex aromas stimulates memories associated with the vintage: Where was I? What was I doing? But the experience can be compromised due to bottle variation resulting from poor storage, a bad cork or inconsistencies in the way the wine was bottled. “A lot of my greatest wine moments have been with great old vintages”, says Richard Brierly, head of Wine Sales for North America for Christies. He adds, “but I’ve had just as many bad ones.” And Marcel Ducasse Winemaker at Third Growth Chateau Lagrange in St. Julien comments, “To me, opening old bottles is not very interesting; except if you are very rich and you can open three bottles in a row to find one good bottle.”

What changes does a wine undergo as it matures and what factors influence a wine’s evolution? What role does cork play in bottle variation? What impact do cellar temperature and humidity have? Why should you be suspicious of an old bottle with a pristine label? Why would two bottles stored under identical conditions taste different? Is a constant temperature desirable or are seasonal fluctuations acceptable and perhaps even beneficial?

Brierly points out that, “Anytime you buy a 40–50 year old wine, you assume risks and you’re going to have bottle variation.” He notes that Bordeaux Chateaux used to bottle barrel by barrel, “now they rack everything from barrel to tank and bottle all at once. There is clearly more uniformity now.” Before modern bottling equipment made bottle variation less common, bottles were filled to different levels, at different times and often at different locations.

Aubert de Villaine co-owner of Domaine de la Romanee Conti comments, “In the old days and we still do it at the Domaine in some vintages, the bottling is barrel by barrel which causes variation not only because one barrel can be different from another but also because the concentration of carbon dioxide is not evenly distributed within a barrel; you have more carbon dioxide at the bottom of the barrel than at the top. If one bottle has more carbon dioxide than the other it will have a different evolution and a different life; maybe more life.”

According to Chateau Margaux Manager Paul Pontallier, bottling of the total production at Château Margaux and other first growths started in 1949, except for Mouton Rothschild which started in the early 1920s. Ducasse cites another factor: “Before the 70s certain Chateaux didn’t bottle at the Chateau but sent the wines in bulk; one barrel to London, another to Brussels and another to Berlin. In these cases there was great variation because of the means of transportation. At Lagrange, just before bottling we blend all the wines from the different barrels into vats to create homogeneity.”

Jean Louis Chave explains the recent history of bottling in Hermitage: “For a small domaine it was very expensive to have a bigger tank only to be used once a year for blending. Most producers were not blending all the barrels into a big tank, but selling the wine when they had orders. At Domaine Chave, until 1982, we were bottling by foudres; the blend was the same but you had wines with different bottling dates, leading to slight variation.”

When Jacques Seysses started Domaine Dujac in 1968, he was the only one in his village of Morey Saint Denis that bottled 100% of the wine at the estate. “In the 60s and 70s, in all the Côte de Nuits there were only six to eight domaines estate-bottling their wines: Gouges, Rousseau, De Vogue, D’Angerville and Ramonet-Prudhon, for example. Today, I can name 5 or 6 in my village.” Seysses recalls simpler days: “I had a corking machine that you had to press a peddle to insert the cork; you filled the bottles by eye and had to be very careful not to overfill.” Winemakers leave a headspace of 10-15mm to allow room for the wine to expand due to temperature increases. James Herwatt, Chief Executive Officer of Cork Supply USA in Napa, California, describes the dangers of filling the bottle to the bottom of the cork: “Any increase in temperature will cause the volume to expand, pushing wine up the side of the cork. If it goes all the way to the end of the cork and out the bottle, air has to get in to replace it. You’ve created an air passage into the bottle.” This extra air space is called ullage.

de Villaine explains that the habit in Burgundy was to leave no headspace. “You don’t want to leave a big headspace because the bottle will lose some of its contents during its life. So as you make wine to last for 30-40 years you don’t want a big gap. But due to concerns about how the wine is transported we now leave a little room for the wine to expand in case of problems during the transportation.”

Because of the vagaries of hand bottling, pre-1975, Brierly finds considerable bottle variation within the same case. “Even within an original wood case of 1961 Bordeaux, stored at proper temperature and humidity, you will absolutely see a range of ullage, from mid-shoulder to right up into the neck of the bottle. Twenty-five years or older it’s really about the bottle itself. Somebody once said, ‘there are no good wines over 25 years old, only good bottles.’ ”

Pontallier disagrees, “I think it is exaggerated. Over the last twenty years I have had the privilege to taste maybe 300 bottles of 1961 Chateau Margaux and the proportion of bad bottles is tiny. A great vintage has a wonderful capacity for bottle aging.” He adds that the vast majority of these bottles had been stored at the Château. “Of course storage conditions can interfere. If you consider that the wine may have traveled the world ten times, that’s totally different.”

Since it has become common practice for winemakers to consolidate all the barrels into a single tank prior to bottling, the most significant source of bottle variation remaining today is the cork. Vernon L. Singleton, Professor Emeritus of Viticulture and Enology at University of California at Davis explains the cork’s role in bottle variation, “Cork comes from the bark of an oak tree. Because of the inherent variability of a natural product, there is going to be a wide range in the amount of oxygen that comes through the cork into the wine. It is therefore difficult to predict that all twelve bottles in a case of wine will age the same—it is likely that they will not.”

The diameter of an average cork is 24mm. The corker compresses it to16mm to fit it into the bottleneck, after which it bounces back to 18mm—the diameter of the bottleneck. Six millimeters or 25% of the cork is pushing out against the glass to create the seal. Cork’s tiny air cells contain suberin, a waxy substance that makes it water-resistant.

Despite this seemingly airtight seal, Singleton believes that air gets into the wine as a result of wine evaporating through the cork. He states, “Water and ethanol are both small, volatile molecules and very slowly evaporate through the cork which accounts for the increased ullage in very old bottles. Since the cork is not pulled in, the headspace must be relieved by an inflow of air.” Evidence that air does get into the wine during bottle aging is the fact that half bottles age faster than full bottles. Since both half and full bottles have the same neck and cork dimensions, the air inflow will have twice the impact on a half bottle.

de Villaine weighs in on the $64 million question, does the wine need air to age? “We don’t actually know very well. I’ve seen bottles with big ullage that were really wonderful and I’ve seen old bottles with very small ullage which were dead. You can’t draw conclusions from looking at the ullage, unless it is very high.”

The lower the cellar humidity, the greater the driving force for evaporation. Herwatt explains how the cork is affected by dry cellar conditions: “Corks can be very hydroscopic; they will gain moisture or lose moisture depending on the humidity in the atmosphere. There is 100% humidity in the ullage space that is keeping the wine end of the cork moist. In a dry cellar, the top of the cork would tend to dry, so there would be an ever so slight migration of wine towards the outside of the bottle.”

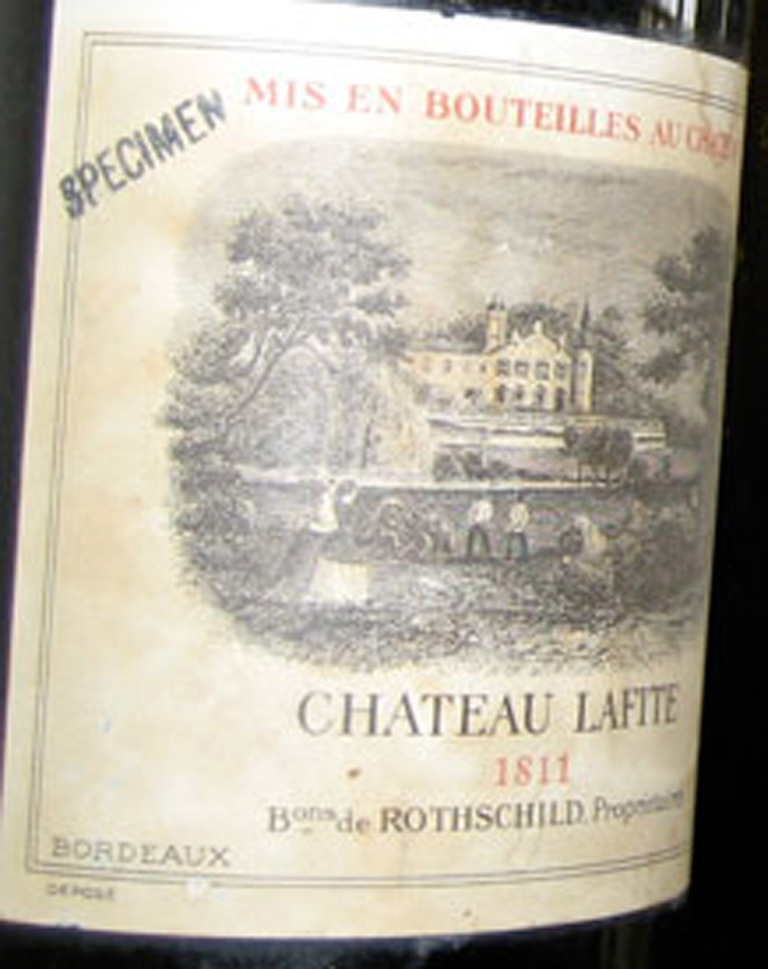

Brierly feels that humidity is as important as temperature: “If possible, I think it should be 70% or 75%. It means that your labels will be a little damp and sometimes illegible, but I’d rather preserve the wine in the bottle than the appearance of the label. Real connoisseurs will take the bad label, as long as the fill level in the bottle is good.”

Seysses, who buys and sells wine at auction, prefers a damp-stained label to a label in good condition, assuming the fill level is correct. “I am more scared of an old wine with a label in good shape,” he adds. de Villaine concurs, “When you evaluate an old bottle a damp stained label is very good. I am very surprised and a little appalled that in the auction sales, the bottles with the perfect labels get a better price than the wines with damages labels, which is completely stupid.”

Until a few years ago, the Domaine would replace the labels on old bottles because collectors would get a better price at auction. “We don’t do it anymore. If I were a collector I would have much more confidence in a bottle with a damaged label than with a good label,” de Villaine comments.

Brierly has found that a low fill Burgundy does not deteriorate to the extent that as a bottle of Bordeaux does with an equal ullage. Referring to Burgundy he says, “They can be interesting and exciting and very palatable even with quite low fill levels,” he says, adding that ullage doesn’t affect the auction price of Burgundy as much as it does Bordeaux. “People tend to be accepting of lower fill levels in Burgundy. They are more willing to take a risk, because they can be extraordinary and because it’s Burgundy—here is so much less of it.”

According to Kevin Swersey of the Connoisseur’s Advisory Group, ullage is more prevalent in Burgundy. “Generally speaking, older Burgundies have more ullage than older Bordeaux. Why? I don’t know. And certainly, the old California wines have the least ullage of any wines I’ve ever seen,” he says.

“As soon as you see a wine get a high rating, the chase is on, but buyers don’t look at the source. The wine could have been in five wine cellars by the time you got it or could have had a bad trip by DHL for one day.”

Higher cellar temperatures not only speed up the chemical reactions that mature a wine, the higher the cellar temperature, the greater the driving force for evaporation of water and alcohol and the potential for the introduction of air.

As cellar temperatures fluctuate, the wine expands and contracts, alternately compressing and relieving the original 10–15mm headspace left at bottling. As the wine increases in temperature, the headspace is compressed, forcing the air out between the cork/glass interface. As the wine cools it contracts, since the cork isn’t pulled in, air is sucked back into the bottle.

How do fluctuations in temperature affect a wine’s evolution? At Domaine Dujac and Domaine de la Romanee Conti, the seasonal temperature variation is 46°F to 61°F. The cellar at Château Margaux varies from 52°F to 65°F between summer and winter and according to Pontallier is typical of the cellars of the other First Growths. These fluctuations may in fact help a wine’s evolution by introducing small amounts of air needed to polymerize tannins, reducing astringency.

There are many elements to consider in the preservation of these older vintages. What’s certain is that the benefit is worth the time and effort. “The most moving part of my drinking experiences,” says Pontallier, “is with old wines; it’s extraordinary, nothing comparable happens with young wines; it’s a different world of complexity and refinement.”