Describing wines in terms of minerality has come into vogue. While the descriptor is over-used and poorly defined, with each taster experiencing it differently, the sensation does exist. Even I find it impossible not to use the term when I taste white wines from the Loire Valley and Burgundy, Riesling from Alsace and Germany, and red wines from Priorat. A wine may be called “stony,” “wet rock,” or “chalky.”

Grégoire Pissot (enologist at Cave de Lugny in Macon), offers a range of terms to describe minerality in Burgundy: “chalk, flint, salty, oil, soil, oyster shell, iodine, or smoky, like when you scrape rocks together.” The problem is that these terms suggest that the source of the taste is minerals in the soil. Since plant scientists say this is invalid then what are we smelling—or tasting? Is it something the vine produces that by coincidence tastes like rocks? Unfortunately, there is no clear scientific answer.

Mineral sensation in wine is assumed to come from minerals in the vineyard rocks and soils, which are taken up by the vine roots and make their way into the finished wine. But plant physiologists say that the minerals are not taken up by the vine roots.

When asked if minerals in the vineyard and the mineral taste in the wine are connected, geologist Alex Maltman (University of Wales, U.K.) replies “No, they can’t be at least not in the direct way that is commonly supposed.” Maltman is not saying minerality does not exist in wine. “The term does seem a useful tasting cue,” he notes. “It is the connotation of origin that is the problem. As soon as people say minerality, they assume there are vineyard minerals in the wine. Sure there are tiny amounts of dissolved ions taken up originally through the vine roots, but these are not the same things as the geological minerals and rocks in the vineyard soil. Vine roots cannot absorb these complex geological compounds. They are largely tasteless anyway.”

Anna Katharine Mansfield (Assistant Professor of Enology at the Cornell Department of Food Science), notes the almost arbitrary use of the term. “Our problem is that we first need to have people agree on what minerality is. Some people use it as a third-tier term where minerality is the term. Some use it as a class of terms. Is it chalkiness, is it stoniness, is it wet rock? Is it an aroma, a taste (such as salt) or a tactile sensation?

“I have been judging on panels with Masters of Wine, sommeliers, and enologists. When someone comments ‘there is really nice minerality in this wine’ we have to talk about what each person means by minerality before we can agree that it is there or not there and whether it is nice or not nice. Right now it is a really trendy word. I am careful not to use the word because it is so poorly defined.”

The term “mineral” can have two meanings. Geologists talk about geological minerals, while plant scientists refer to mineral ions, also called mineral nutrients.

Geological minerals are chemical compounds; they are the minerals in vineyard rocks and soils. Mineral ions or nutrients, on the other hand, are the components of geological minerals. Vines require 16 mineral nutrients to complete their annual life cycle. For example, feldspar weathers into its component mineral elements sodium, potassium, aluminum, calcium, silicon, and oxygen.

Do grapevines take up these geological minerals, which in turn impart a mineral character to the wine? Scientists say they do not. “The vine is unable to take up these minerals,” explains Carole Meredith (Professor Emerita in the Department of Viticulture & Enology, University of California, Davis). “A mineral is a complex chemical compound and when it gets in the area near the plant roots it is broken down into its component ions. Grapevines never take up a mineral, only the components of minerals.”

Although the component ions can be taken up by the roots as they are needed by the growing vine, only a certain proportion of mineral ions end up in the grape. A portion of those that do end up in the must are used by the yeast during fermentation. Potassium is lost as potassium bi-tartrate crystals during ageing.

Meredith adds that the plant is not just a passive filter. “What the plant puts into its fruit that eventually ends up in the wine is highly controlled. There are membranes in the roots and all throughout the vine that specifically allow some things through and exclude others. Just because a plant takes something up from the soil does not mean it gets into the fruit.”

Maltman notes that the concentrations of minerals (nutrients) in wine are too low to taste. “Inorganic mineral elements make up only around 0.2% of a wine. In these concentrations we simply cannot taste them, even in distilled water let alone among all the aromatic organic compounds that give wines their flavor. For example, copper is typically present in concentrations of 1.5mg/l. Its taste threshold in water is 3 mg/l. So for us to taste copper, the concentration in water would have to be 2,000 times greater and massively more in wine.”

Tasters often define minerality as the smell of wet rocks following a summer rain. But rocks do not have an odor, so what are we smelling? According to a paper written by Australians J. Bear and R. G. Thomas in 1964, after a rain what is assumed to be the smell of rocks is petrichor—the scent of organic compounds that were released from plants and fell on the rocks and soil during dry periods.

Mansfield explains, “The authors suggested that when it rains, volatiles contained in the dried plant material are released, so what you are smelling is not the rock itself but a compendium of all the plant life around those rocks which is kind of an interesting argument for terroir. You are only smelling organic matter that has settled on the rock; if you get a really clean rock it does not have a smell. The authors called this rock aroma or rock essence petrichor, and it would vary based on the kind of plants around the rocks.”

Gavin Sacks (Assistant Professor of Enology at Cornell) makes an important clarification: “A rock and a mineral are not the same thing. A mineral is an ordered solid with a well-defined chemical structure. A rock is composed of one or more minerals, but may also include organic matter think about oil shale, as an extreme. Usually we encounter rocks in nature, not minerals. Rocks could certainly have a smell; it is just not the mineral part we are smelling.”

Christophe Rolland (ex-sommelier at the Bellagio in Las Vegas, Alain Ducasse in Monte Carlo, and L’Auberge de l’IIl in Alsace) finds minerality in wines from the most northern vineyards where you have a single grape variety. “In regions such as Alsace and Burgundy, the soil has a tremendous impact on wine character. In Champagne, especially with Chardonnay, you also have tremendous mineral quality. The carbonation I think brings this quality out. But you have to work with a small grower who works in a particular area or with a négociant who works with a specific area. Champagne is harvested at low maturity and high acidity, which works in favor of minerality.”

Rolland mentions the one point where there is agreement—the relationship between acidity and minerality. High acidity is one of the necessary conditions for the expression of minerality. “I think the acidity reinforces the minerality. High acid vintage like 1996 or 2002 in Burgundy provide more support for the minerals. Minerality can be fragile. When you do lees stirring, you try to enrich the wine, but you lose some of the vivid, crisp, pungent character that provides that edge, which is more in phase with the minerality of the wine and less with the buttery, rich, waxy, honey character.”

Pissot concurs, adding that the term “mineral” is, at times, used when “acid” would be more appropriate. “In my opinion, the mineral flavor is indeed linked to the level of acidity. All the vineyards mentioned are in northern Europe, with colder climate, therefore with sometimes under-ripe vintages. This is why the ‘mineral’ quality is sometimes misused by people, describing a wine as ’mineral’ instead of under-ripe, or ‘acid,’ in order to improve the description of the wine.”

Mansfield says that the relationship between acidity and mineral flavor is “a good hypothesis, but just a theory at this point; some suggest that it is a combination of a lack of fruitiness and high acidity.”

Rainer Lingenfelder (Germany’s Pfalz region) says, “It certainly has nothing to do with what one can mea- sure as potassium, calcium, magnesium, boron, or whatever in the wine. It probably has more to do with acidity and actually a certain ‘un-ripe- ness.’ People find minerality in our wines, more in the ones with higher acidity. I myself ... use the term very rarely, as it is much less apparent in our conditions (and soils: sand, loess, and chalk ?? ... is there some connection to the soil after all?? Well, I guessour sites just produce ripe fruit on a regular basis.

“The grape variety also makes a difference. It is true that Riesling shows more minerality than Scheurebe even when they grow side by side. Riesling has more acidity than Scheurebe—this is probably the reason. I find more ‘minerality’ in Saar wines than in Rheinhessen or in Pfalz where I am from.”

Nik Weis (who runs the Mosel estate of St. Urbans-Hof) concurs. “Especially when acidity is part of the game, minerality comes out more. My Ockfener Bockstein located in the Saar is a higher acidity wine and shows more minerality than my Piesporter Goldtröpfchen. The Ockfener Bockstein is embedded in a mountain range. At night the cool air flows from the mountain down into the valley. The Piesporter Goldtröpfchen does not have that kind of a chilling effect; it is always fairly warm.

“In addition to these climatic temperature differences, the two vine- yards have different soil composition, which affects the amount of heat the vines receive. The soil in the Piesporter Goldtröpfchen is a highly decomposed dark blue Devon slate, which makes it heat up easily. The soft and waxy structure retains the warmth long into the evening. In the Ockfener Bockstein you find a grey slate soil with very hard and solid rocks, which also have some quartz enclosures. The acidity is more preserved here than in Piesport.”

Mineral expression appears to come less from the soil’s mineral composition and more from the climate and how the soil’s physical characteristics influence ripeness and therefore acidity.

Meredith agrees with the acidity thesis, “Minerality is probably related to the perception of tartness. Lean, tart wines have this. Why people call that ‘mineral’ is probably just convention and may not have anything to do with real minerals at all because I do not think people have a clear idea what minerals taste like.”

Mineral character is most frequently cited in wines grown in limestone-rich soils; as if the chalky sensation one finds in Chablis or Riesling in Alsace is derived directly from the soil. In reality, limestone soils are alkaline and produce wines with higher acidity, explains Marc Dubernet (who has a doctorate in enology and has managed Laboratoire Dubernet in Narbonne, France for 40 years). “The favorable terroirs for the appearance of minerality are those that bring together a cool climate with a good late growing season and alkaline soil types (chalk, limestone, etc.). It is well-known that, for any given climate, alkaline soils lead to high acidity and low pH in wine, while acidic soils lead to must with lower acidity and higher pH.”

Dubernet adds that while the acidity level is important, the balance of organic acids in wine is fundamental. “It is clear that malic acid plays an important role. Its taste is decidedly more ‘mineral’ than that of tartaric acid. A higher amount of malic acid at harvest time will always be a favorable factor for minerality.”

Weis describes minerality as less of an aromatic and more of a taste quality. “Minerality is not something that you smell. It is much more a salty impression that has an effect on the way the acidity comes along or the sweetness. I describe minerality in terms of saltiness, when a wine has a salty finish just like some mineral waters do. The salty characteristic is always derived from minerals in the soil.

“For example, when you talk about chalky minerality that would be something you would find in a Chablis or a white wine from the Cote d’Or, whereas in the Mosel we have a kind of ashy minerality which definitely comes from the slate soil. I think that the minerality in the Saar, where I am from, comes through in a different way, maybe even stronger, and the reason for that is the mostly hard gray slate soil with quartz and some iron veins. In some parts of the Saar there is so much iron that the slate has a reddish color, a rusty red.”

Weis adds, “Even more so it influences the mouthfeel of a wine. The minerals in Mosel Riesling allow us to leave more sugar in the wine to balance out the acidity and it still finishes dry.” The sweetness is offset by the saltiness the margarita effect. The salt around the rim of the glass is important; the acidity of the lemon or lime and sweetness alone would make it taste just sweet and sour. The salt creates a feel of effervescence, a feel of refreshing spritz.”

Determining whether minerality is a taste, smell, or mouthfeel sensation may prove to be more difficult than one would think. Dr. Larry Marks (Fellow of the John B. Pierce Laboratory and Professor of Epidemiology and Psychology at Yale University) explains, “When you take something into your mouth you try to figure out what part of it might be smell; that is very hard to do, even with practice.

“If you take something fairly simple, vanillin, the essence of vanilla, at low concentrations, even though it does not stimulate taste receptors at all, people will put it in their mouth and say, ‘Gee—it tastes a little sweet,’ even though there is no activation of sweet receptors. You put in a little sugar and they say, ‘That is a really good sweet vanilla taste.’ They cannot determine which part of it is taste.

“The flavor of anything taken through the mouth has an enormous number of components. It is a complicated and poorly understood interaction among gustatory response (taste), olfactory response (smell), and somatosensory response (touch, mouthfeel). You want to tease these apart but you cannot do it just by reflecting on your experience. If we could do that we would never have had to build laboratories, and even with laboratories it is hard to figure out.”

Do chalk, flint, or slate soils impart chalky, earthy, flinty, gravelly, or slatey characters to a wine? Meredith believes the origin of minerality is more complicated. “It is something that the plant is doing in response to its total environment, which will include the soil, but also the air and the temperature and the wind and how it is farmed. The plant ends up producing the things that you taste; it is not just transferring them from the soil into the wine. You have to give the plant more credit; it is not just a passive conduit for the things in the soil.”

Weis believes mineral flavors come from constituents in the soil, “I do think that minerality comes from the soil. These minerals influence the metabolism of the yeasts and therefore the fermentation flavors in a wine.”

Maltman suspects that although the concentrations of inorganic ions derived from the vineyard soils are tiny, they might influence organic chemical reactions involved in vine growth and during vinification. “It could be some combination of the resulting organic compounds rather than the ions themselves that give what people call a minerality taste,” he suggests. “In other words, there could be a connection between the vineyard geology and minerality, but in a way that is very indirect and complex—and at present unknown.”

“There is an absence of hard data showing that what we call ‘minerality’ correlates to certain levels of specific minerals or ratios between minerals, or perhaps even in specific redox couples,” says Randall Grahm (Bonny Doon Vineyard, Santa Cruz, CA). “Probably the disulfide/thiol couple is the one that is most interest- ing, as that is the one that is in our sensory wheelhouse.” Here Grahm is touching on an interesting idea: that reduction can show itself in a form that leads to the use of the “mineralic” descriptor by tasters. Overall, he thinks that minerality in wine has many sources, and that it correlates with this list of phenomena:

“It is certainly possible to confute ‘minerality’ with other phenomena,” adds Grahm, such as “the presence of Brettanomyces (that is more iodine and sweat), ‘greenness’ (that is likely green seeds or perhaps inclusion of stems), tannin (that is more of a sense of astringency), and various volatile sulfur compounds such as thiols and disulfides.” In relation to the last point, he adds a question: “Do minerals in wine tend to make a wine more backward or ‘reduced,’ or is a tendency toward the formation of thiols just another word for minerality?”

The lexicon of wine is full of abstract terms that are hard to define. What is a “layer” of flavor? What exactly is a wine’s “mid-palate?” It is ok for scientific fact and romance to comingle? But minerality is important and different. As a major component of some of the world’s greatest white wines; it has become a code word for high quality.

Its popularity could be a backlash against the big, oaky, buttery style. As wine drinkers become more sophisticated, they are attracted to wines that reflect a place rather than the hand of the winemaker. Minerality is one way to associate a wine with the vineyard or region in which the grapes are grown.

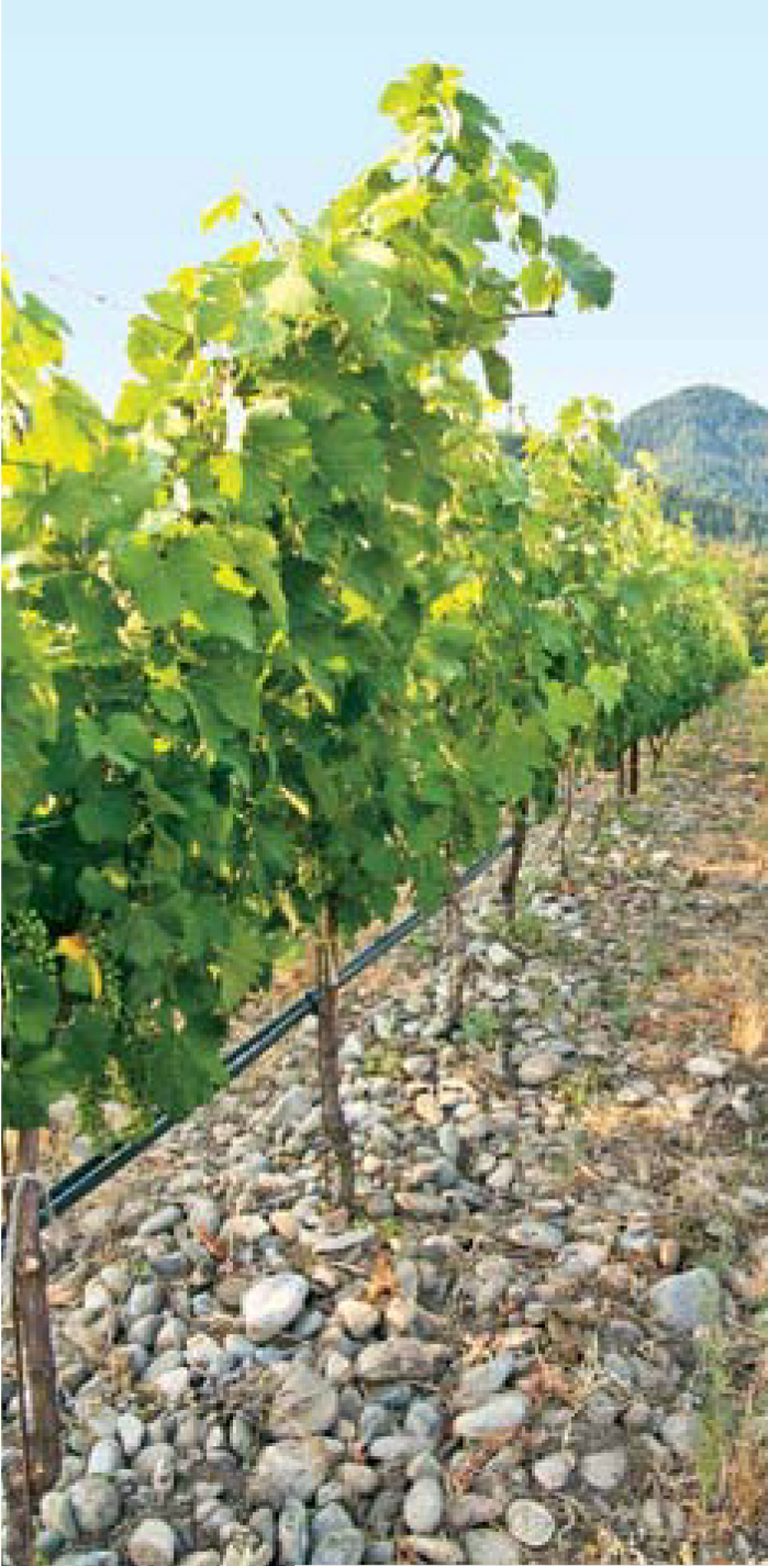

Since how a wine tastes is a combination of so many factors, some of which are impossible to measure, we look for something tangible, like rocks, to explain what makes a wine distinct. It is easy to oversimplify and draw the wrong conclusion. Rocks, rather than directly imparting flavor, play a more important role in a soil’s physical structure, which affects how water is made available to the vine.

Minerality is an actual sensation, but whether it has anything to do with minerals in the real world is doubtful. It is a bit of an abstraction—part romance, part reality, a moving target, different from region to region and even within a region.

Arnaud Saget (who produces Domaine de la Perrière Sancerre and wines from nearly all Loire Valley appellations) feels that Pouilly, Sancerre, and Savennières are the three dry appellations that show the best expression of minerality; but not the same minerality. Saget explains, “Each appellation expresses minerality in different ways. While Pouilly gives more impression of ‘crunching’ on a rock, Sancerre shows more elegance and more purity. Savennières sometimes shows an expression of minerality very close to some Rieslings from Alsace, with petroleum aromas.”

Minerality probably does not describe a specific sensation but a class or category of sensations found in wines with high acidity and low fruit expression; although the fruit- scented German Rieslings are an exception to that rule. Because it has become associated with high quality, we tend to look for it.

Since so much of perception is based on expectations, we tend to find minerality where we think it should be. The next time you open an austere white wine with high acidity, choose your words carefully.

—Practical Winerty and Vineyard Journal, Winter 2002