California’s top winegrowers are used to taking the moral high ground when explaining the quality of their wines in low-tech terms such as gravity flow, minimal intervention, low yields and wild yeast fermentation. They don’t like to take a back seat to someone with a “holier than thou” attitude employing a technique they do not. Which is why they resist efforts within their own ranks to promote organic farming.

There is hardly an issue in wine today that provokes more emotion, opinion and controversy than organic farming. Both sides are guilty of stereotyping the other: non-organic farmers view organic farming methods as riskier resulting in lower yields with the potential for significant crop loss. Certified organic growers—who use only naturally occurring products—believe non-organic growers over-fertilize, over-irrigate and are indifferent to the environmental effects of herbicides, fungicides and insecticides.

There is hardly an issue in wine today that provokes more emotion, opinion and controversy than organic farming. Both sides are guilty of stereotyping the other: non-organic farmers view organic farming methods as riskier resulting in lower yields with the potential for significant crop loss. Certified organic growers—who use only naturally occurring products—believe non-organic growers over-fertilize, over-irrigate and are indifferent to the environmental effects of herbicides, fungicides and insecticides.

The truth is there is a continuum of non-organic growers—at one extreme there is little that separates non-organic growers from organic growers. “I would say it is only very tiny issues that separate an organic from a non-organic farmer. Those who are latching onto it from a marketing perspective want to polarize the issue and make more of it that it really is. It’s not either/or. I think all good farmers are as organic as they can be,” says Dave Ramey, winemaker at Rudd Estate in Napa.

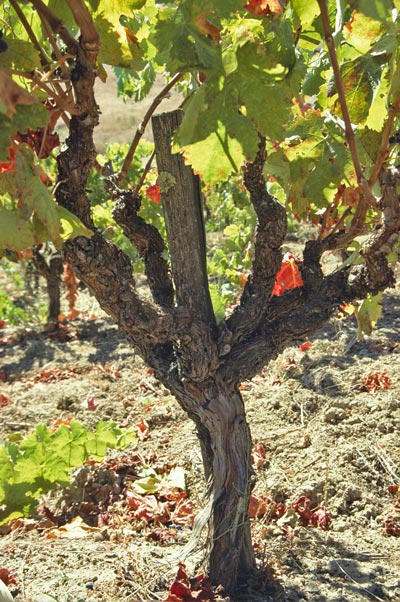

Winemakers are becoming more and more organic whether they are certified or not in their wine production practices. The debate is likely to intensify because more winemakers are planting experimental organic plots due to the merging of different trends: the realization that great wine is made in the vineyard and therefore the vineyard—especially the soil—must be treated as the winemaker’s primary asset. As never before, new vineyard plantings are encroaching on residential areas forcing growers to be more conscious of the societal and environmental effects of their farming practices. And finally—and most controversial of all- is the idea that to show terroir, the use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides must be eliminated.

All of this raises questions. How can successful growers and winemakers hold such divergent views on farming? Are organic farming practices the secret sauce to more flavorful wine or are they just better for the environment? And are all organic methods necessarily better for the environment? In an increasingly competitive wine market, are organic farmers creating buzz to sell wines? Do you need to eliminate the use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides to show terroir?

One practice that separates non-organic from organic growers is the use of Roundup. The controversy surrounding the use of this herbicide is symbolic of what are for the moment irreconcilable differences between the two camps. Roundup is a weed killer which is sprayed in the vine rows. By keeping the area clear of growth, burrowing animals and insects will not have direct access to the vine’s roots and foliage. The organic side—bolstered by their own research—believes that Roundup residues persist in the soil long after application, is toxic to beneficial soil microbes and earthworms, can leach into ground water and that the producer, Monsanto was indicted for falsifying data in getting Roundup registered. The non-organic side—citing their own research—believes Roundup is a benign chemical that rapidly bio-degrades, doesn’t get into ground water and cites research that Roundup has only temporary and therefore inconsequential effects on soil microbial life.

Hampton Bynum of Davis Bynum Winery explains why maintaining bio-diversity—a multitude of soil microbial life as well as insect and plant life is an important tenet of organic farming, “We had an aversion to using herbicides, fungicides and insecticides since the beginning, based on the idea that you go in and start messing with the ecosystem, pretty soon you're going to be creating as many problems as you're solving.” An insecticide may eliminate a problem insect but if it inadvertently wipes out a beneficial insect that was feeding on another pest, you’re back to where you started. Organic growers claim that by maintaining bio-diversity, the vineyard is less vulnerable to attack by predators such as the blue green sharpshooter which transmits Pierce’s Disease. The more uniformly an area is planted to a single crop—let’s say grape vines—the more rapidly a disease or pest can spread. Conversely says the organic farmer, the greater the variety of resistant plants or other crops planted in and around the vineyard, the more slowly the disease or pest will spread. Bio-diversity is used a tool in organic farming which explains the use habitat ditches and insectary plants. Habitat ditches contain vegetative material that is more attractive to a leafhopper than a grape leaf. Insectary plants attract birds and insects that will in turn feed on leafhoppers.

Daniel Schoenfeld of Wild Hog Vineyards has been certified organic since he started growing Pinot Noir and Zinfandel on the Sonoma Coast in 1981. He comments, “The biggest reason to farm organically is because it is the right thing to do, right in terms of the earth and your neighbors. I don’t want to have poisons around the area that will be upsetting my neighbor and I just don’t think the stuff is good for the earth. As farmers, we are caretakers of the earth it’s our duty to tread as lightly as possible.”

But non-organic methods are not necessarily inconsistent with safeguarding the environment. Ted Lemon of Littorai states, “I think what’s important is trying to become better stewards of the earth. The issue is what is the least impact you can have, whether that is in organic of non-organic farming. It may be that generations down the road there will be studies that say when you look at the global effect of going through your vineyard twice as many times with an internal combustion engine, that’s the greater impact -- that’s as non-organic as it gets.”

Lemon buys Pinot Noir and Chardonnay from numerous growers and would not necessarily pay more for organically grown grapes. He says, “If the choice is between buying from a farmer who is organic except that he sprays Roundup or one fungicide at the end of the year versus buying grapes from an organic farmer who is a poor vine tender and who over-fertilizes with organic products and doesn’t do proper erosion control, I’ll take the non-organic. If with an organic program you have to run your tractor through your vineyard five or ten more times a year with the resulting use of gasoline and the combustion engine and compaction of the ground, I’m not sure that’s better.”

As Lemon alluded to, in order to protect their vines from mildew, organic farmers have to spray their vines more frequently than non-organic farmers who have an array of synthetic products available. Synthetic products are “systemic” meaning they enter the vine and provide more long-lasting protection. Organic sulfur has a very short life—when you make an application of a sulfur product today, everything that grows out afterwards is unprotected. The late Warren Dutton—criticized by some for his conservative farming practices and lauded by others as a highly successful grower—planted his first vines on the Sonoma Coast in 1965. Dutton tends 1,000 acres most of which is Chardonnay, he commented, “To me, there is a high risk of organic farming. To be certified organic is like driving around in a Model A—a huge amount of extra work and extra cost. You could do a program that is 90% organic and have a huge reduction in the amount of materials you are using.” His practices are not only a result of his attitudes about farming but also the grape variety he is growing—Chardonnay which is susceptible to mildew—and where he is growing it—on the Sonoma Coast Chardonnay where mildew pressure is high.

Dutton added, “I want to reduce my input into the vineyard, that's my reason for not growing organically. I think reduced input is more important than being organic.” He cited a new product on the market this year to control mildew that he claims is people safe, water safe, environment safe, “It’s a naturally occurring substance found in plants but since they make it synthetically it's not an organic product. You can use two ounces of it per acre, whereas if you are organic, you'd be putting on fifteen pounds of sulfur per acre. So if you use this product you can no longer call yourself organic but you've just made a one-time application reduction of over fourteen pounds of material per acre. If you're choosing reduced input rather than full-on organic, I think you're making a better choice for the environment.”

Schoenfeld is not saying organic practices are the secret sauce to wine quality. He says, “In my personal experience, I have noticed hardly any difference between wine made from organic grapes and wine grown conventionally. I’ve had absolutely horrible and wonderful wines made from both. For example, our Saralee’s Pinot Noir—Saralee uses a pretty full compliment of chemicals in her vineyard—is absolutely delicious, just as nice as our estate Pinot Noir. It’s a little different, but I wouldn’t say it’s a lesser wine because she uses chemicals. The advantage to our wine is that it was grown organically and we’ve done perhaps less damage to the earth in the process. I wish I could say ‘organic fruit made a much better wine’, I have not experienced that to be true.”

John Williams of Frog’s Leap has been certified organic for 11 years and views organic farming as much more than an environmental issue. He explains, “The only reason to farm organically is to improve wine quality. The reason the best chefs in the best restaurants in the country are using organic fruits and vegetables is because they have more flavor. My hope is that it doesn't become trendy because it's organic but that it becomes an accepted method because it's a good for wine quality.”

Despite the widespread perception among chefs and consumers that organic food products taste better, it has not been proven that organically grown grapes inherently make better wine. Lemon states, “It’s all about taste and I don’t know how you can demonstrate from a taste perspective how organically grown grapes are better. Winemaking and grapegrowing are such complex and multifaceted undertakings that you can’t just arbitrarily pull out the fact that you’ve gone organic as the reason you’re making better wine.”

The subject of terroir swamps all others these days: how accurately does a wine reflect the soil, climate, growing conditions of a vineyard. The majority of California Chardonnays for example, do not show terroir because there are so many winemaking factors that can mask terroir—oak, sur lees, battonage and malolactic. Ironically, it is these processing flavors which win blind tastings. Believers in terroir say that the wine may be good but it is not representative of the vineyard—it does not reflect the soil. What difference does that make; the wine scored 90 points and is sold out.

Williams is troubled by the standardizing of wines worldwide toward a uniform style but sees it changing at the restaurateur level, “They're getting tired of wines with tremendous alcohol, oak and tannic structures and no individual personalities. You can take a lot of the big name Napa Valley Cabernets, top Bordeaux and Super Tuscans, line them up on a counter and you have a better chance of telling who made the barrels than what country they came from. That style of wine diminishes the much more subtle influences of terroir, the natural conditions of where the grapes were grown. If we don’t care where the wine was made, that's fine—but I want to make wines that taste like Rutherford.”

Davis Bynum Winery has always grown grapes organically, but hasn’t bothered to become certified. “The added complexity, the vineyard characteristic above and beyond the fruit, give an added dimension to the wine. My wines show terroir more than my neighbor's,” Bynum remarks. Bynum is critical of what he views as the non-organic growers’ cavalier attitude toward the soil, “the person who has bought the whole agrochemical package uses soil as a media in which to grow grapes, as opposed to an entity in and of itself. You try to neutralize the soil to the greatest degree possible and then you start to add the desirable nutrients back.”

There might be a connection between organic farming methods and the expression of terroir but it has yet to be proven, as Lemon explains, “As for organic farming showing terroir better, it sounds great but I’d like to see someone demonstrate it.”

Even after hearing from those with knowledge and experience, the questions raised earlier are not easily answered. What do we conclude is the right approach to farming? We do know that as pressure mounts from the environmental community, organic farming is becoming less a fringe practice. As non-organic farmers adopt more organic techniques, the gap between the two sides closes. So one has to be skeptical about claims of superiority from either camp. As with other trends that have swept through the wine industry such as wild yeast fermentation and the use of fining and filtration, it is important to be objective about organic farming’s benefits – perceived or real. Lemon adds a cautionary note, “to be railroaded into organic farming because it is politically correct rather than based on sound science would be a disservice to succeeding generations who will face even tougher and more complex environmental problems than we do.”

—By Jordan Ross, Global Vintage Quarterly, Fourth Quarter, 2000