The fungi are a fascinating group of living organisms. More than 100,000 species have already been identified and twice that number may exist. One particular fungus, Penicillium roqueforti was first found in caves near the French village of Roquefort. As the story goes, a piece of cheese was left in a cave and a few weeks later was found to have acquired a tart, pungently fragrant character from the fungus infection. Today, only cheeses from around these caves can use the name Roquefort. Similarly, the fungus Penicillium camemberti give Camembert cheese its unique flavor.

There is a group of over 50 different parasitic fungi that grow on grapes producing what is called bunch rot. Even though growers spray to avoid bunch rot, moldy grapes are responsible for considerable crop loss each year. Bunch rot organisms emit unpleasant odors. Sour rot, a bacterial/bunch rot complex produces acetic acid imparting a vinegary smell. Aspergillis growth gives off a “smelly sock” odor while Penicillium smells just plain rotten making these grapes unsuitable for winemaking. These three common bunch rots are called secondary pathogens because they can grow only where a crack already exists in a grape due to insect or bird damage or where grapes split from growing too closely together in a cluster.

While bunch rot is the bane of the winegrower’s existence, there is one fungus, Botrytis cinerea that is required to make some of the world’s most delicious and expensive dessert wines. Botrytis cinerea is a primary pathogen because it can attack undamaged fruit. Under normal conditions, Botrytis bunch rot is responsible for annual crop losses of 1–10% in California. However, the proper set of climatic conditions transform this lowly bunch rot into what is called ‘noble rot.” The healthy grapes become shriveled and fuzzy, providing the raw materials the decadently sweet Sauternes of France and the exotic Trockenbeerenauslese and Berenauslese of Germany, as well as others.

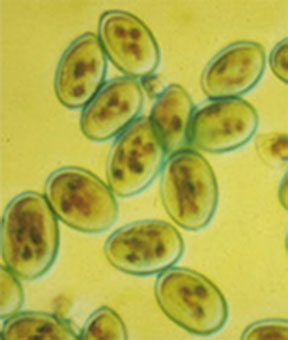

Botrytis cinerea as seen through the light microscope.Botrytis cinerea as seen through the light microscope. Each country has its own traditional grape varieties: Semillon and Sauvignon blanc in Sauternes, Chenin Blanc in the Loire, Riesling in Germany and all of the above including Gewurztraminer in California and Australia. These varieties are more susceptible to bunch rot either because their thin skins are more easily pierced by the fungus or have tight clusters causing poor air circulation between the berries. Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon for example, are thick-skinned, loose-clustered varieties and are therefore less prone to rot.

The Botrytis spores are present in the vineyards throughout the year but remain dormant until the proper weather conditions prevail: a combination of cool temperatures and high humidity. A common scenario is for morning fog from a nearby body of water to settle on the grape surface initiating an “infection.” The fungus pokes minute holes in the skin of the berries allowing water to evaporate, causing shriveling. Extremely hot weather (above 90°F) will dry up the infection altogether and cause raisining. Continued wet weather or high humidity following the initial onset of Botrytis results in a mixed bag of fungal infections without the simultaneous dehydration of the fruit.

Under ideal conditions, the afternoon sun dries up the moisture halting the growth of Botrytis and causing desiccation as water evaporates from the grape pulp. After this cycle of morning sun and afternoon fog continues for 3–10 days, the grapes dry and shrivel into what resemble fuzzy raisins. The clusters, portions of cluster or even single berries affected with noble rot are harvested individually, hence the term, special select late harvest. If temperature and humidity remain favorable, further noble rot occurs and successive harvests are made.

Dirk Hampson, Winemaker at Dolce, a winery founded by Far Niente in Oakville, produces a fine late harvest blend of Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc. Hampson started out in 1985 making six barrels for fun only, and now produces 65 barrels. He explains, “On average, we pick a vineyard five to six times, picking clusters, parts of cluster or single berries. The selection process is perhaps the most important step because when the conditions are right for Botrytis they are also right for other undesirable bunch rots.”

Not only must specific weather conditions prevail, but they must do so at the right time of the season. Jim Klein, who makes late harvest Riesling at Navarro Vineyards in California’s Anderson Valley says, “The timing of the rain is critical. The rain must arrive when the grapes are at full maturity of 22-25% sugar. Below 20%, there is too much acidity in the grape. In 1992, the rain came when the grapes were at 19% sugar so the Botrytis just concentrated acid not sugar.”

Of the 20,000 cases of wine Navarro produces annually, a maximum of 4,000 cases will be late harvest dessert wine. “Our location in Northwest Mendocino County just six miles from the Pacific Ocean provides the moisture and cool temperatures which Botrytis likes. When the conditions are right, the Botrytis just takes off and the wines almost make themselves,” says Klein

When the right combination of humidity and temperature do not exist, can you create them artificially? Klein answers, “It doesn’t do any good to force the issue. We have tried overhead sprinklers and spraying Botrytis spores directly onto the clusters. We got black rot and other bunch rots but no Botrytis growth.” It appears you can’t fool Mother Nature.

Don Van Staaveren, Winemaker at Artesa Winery in Carneros, has been up to his elbows in Botrytis since l974 when he began making dessert wines from Riesling with Richard Arrowood at Chateau St. Jean. He comments, “Alexander Valley is not a cool growing area and in theory Botrytis should not be found there. But I feel that the humidity level inside the canopy is more important. Three of the Botrytis vineyards, Hoot Owl Creek, Belle Terre and Frank Johnson all got fog from the Russian River providing plenty of humidity.

Van Staaveren agrees with Jim Klein about the importance of the onset of the Botrytis infection with regard to maturity levels adding, “It is critical that the infection occurs near maturity with respect to sugar and acidity. Wines made from early Botrytis are sour because the balance isn’t correct inside the berry. At 20-23% sugar, the Botrytis has ripe fruit flavors to work on and concentrate. Also, the infection must be clean Botrytis because other bunch rots have a mustiness or moldiness like a stinky piece of cheese.” Hampson also agrees, “I am a proponent of getting ripeness before Botrytis. Botrytis flavors are best when they are in harmony with ripe fruit flavors.”

Chateau St. Jean makes late harvest wines every year. Van Staaveren comments, “We started out the year intending to make some. We gave Botrytis every opportunity to happen. We evaluated its progress during the summer and when we found a point of infection we tried to promote it by increasing irrigation, eliminating fungicide spray and leaf removal and hope for the best.” Van Staaveren recalled with excitement Chateau St. Jean’s commitment to German-style late harvest wine production, “We were the only winery in California that actually planted a site for Riesling. We picked the clone of Riesling and the trellis system. The vineyard was adjacent to the Russian River, surrounded by trees. The river gave us the humidity which stays in the vineyard because the trees restrict air movement.” Navarro has also planted an acre of Riesling dedicated to the production of late harvest Botrytis wines. “We intend to plant an additional ten acres over the next three years experimenting with three different clones,” says in Klein.

But the number of acres planted to Riesling has fallen off, and so has the production of the late harvest botrytized nectars. Today, a ton of Riesling grapes costs about $650/ton and the wines sell for $10–$15 per bottle. Because of the greater return (it costs nearly the same to farm an acre of grapes regardless of the variety) growers have steadily pulled out Riesling and replanted with Merlot, Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon which fetch $l,500–$4,000/ton and sell for $l5–$100 per bottle.

Craig Williams, Joseph Phelps’ veteran winemaker recalls the heady days of the l970’s when Riesling was king. “When I left U.C. Davis in l975, everyone made a Riesling. It was the most expensive grape at $l,000/ton; Chardonnay was $600–$700/ton.” Williams has resisted the temptation to pull out the Riesling. “I thoroughly enjoy making the late harvest wines. We made our first Botrytis wine from the Stanton Vineyard in Yountville in 1975. At that time Walter Schug at Joseph Phelps, Dick Arrowood at Chateau St. Jean and Jerry Luper and Brad Webb at Freemark Abbey were the leaders in drawing attention to what had heretofore been considered a rot and dumped back into the vineyard. It was their creativeness and vision to take these grapes and make what is now the industry standard for dessert wine.”

Yountville’s proximity to San Francisco Bay provides both the cool temperatures and high humidity necessary for Botrytis. What is unique to California is that it is dry in terms of rainfall but certain locations in the Napa, Sonoma and Mendocino counties get fog and cloud cover until noon due to the marine influence. This fog, thick enough to be mist, rests on the grapes stimulating Botrytis growth.

Like Hampson at Dolce, David Ramey, while winemaker at Chalk Hill Winery in Sonoma County, also produced a Sauternes or Barsac-style dessert wine from a blend of Botrytis-affected Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc. Ramey, a lover of French winemaking traditions and practices comments, “Semillon-based wines have a distinct structure and balance. The classical constructs in France dictate harvest sugar of 30–34% yielding wines of l4% alcohol and acidity of 7–8 grams/liter. If harvest sugar exceeds these levels the yeast are unable to produce enough alcohol to give the power and structure expected of a Sauternes-style wine. If you’re working with Riesling (alcohol levels of 7–9%), there is no upper limit to harvest sugar, which suits the California attitude of “if a little is good then more is better.”

Preferences aside, there are fundamental differences between dessert wines made from Riesling and those produced from Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc. Riesling (and Muscat and Gewurztraminer) is high in a class of highly aromatic compounds called terpenes which give Riesling its flowery and honeysuckle scents. Semillon is more neutral, says Ramey. “Just as Chardonnay is a blank pallet for oak and malo-lactic, Semillon by itself is kind of bland and is a blank pallet for Botrytis, giving Semillon-based dessert wines aromas of peaches and apricots as the fungus concentrates the grape’s contents.”

Hampson’s motivation for Dolce, which is 60–75% Semillon and the remainder Sauvignon blank was simple, “I chose the Sauternes style because I considered it the most challenging and therefore the most fun. The German-style wines are bottled 3–6 months after harvest reflecting the fruit of that year versus Sauternes which is more a reflection of wine making influences.” Dolce follows the time-honored winemaking practices of Chateau d’Y Quem, the world’s most famous and expensive dessert wine. Hampson ages Dolce in l00% new oak barrels for three years and use the tightest grained oak available.

The trademark viscosity of these wines comes from the high sugar concentration as well as the fungus’ production of large quantities of glycerin. This viscosity not only adds to the satiny mouthfeel of late harvest wines but also causes some of the many difficulties associated with their vinification. Besides attracting bees, making harvesting hazardous, the high sugar musts are a difficult environment for the yeast to grow in. Fermentation may be difficult to start and may require several months to complete compared to a week for table wine fermentation. The finished wines are so thick that they are difficult to pump and clog conventional filters.

Another attribute of these late harvest wines is their dark color. Botrytis mold produces an enzyme that causes browning, giving the wines their yellow color, which intensifies to a golden hue as they age. Dessert wines made from botrytized grapes have considerably greater aging potential than table wines. Like Madeira and Port, the high sugar concentration preserves the wine against microbial growth as it ages in the bottle or after it is opened.

The aromas alone are seductive and the taster derives great pleasure from simply smelling the rich apricot and honeysuckle perfume of a late harvest wine. The intense sweetness followed by the scintillating jolt of acidity makes the wine drinker’s mouth gush with pleasure. Why else have these wines been given the accolade, “nectar of the gods?”

—Wine & Vines, October, 1994