The fact that the FBI was in the office bright and early to seize files wasn’t an immediate concern to me. I wasn’t afraid of being handcuffed or anything. The Feds were checking numbers on the big brokers—not the little guys like me.

I had spent three years making 300 calls a day, selling speculative, over-the-counter stocks. I had index cards posted all over my cubicle, with answers to every conceivable objection.

But I came to the point where I no longer believed that analysts could pick stocks that could hold their value, let alone “light up the sky.” I was disenchanted with a career on Wall Street.

Fortunately, I had been nurturing a keen interest in wine. The interest grew into a passion when a group of savvy wine lovers from the office invited me to one of their monthly tastings. I remember being tantalized by the likes of Ridge Vineyards, Heitz Wine Cellars and Joh. Jos. Prum.

My fate was sealed when I took an inspiring class taught by a graduate of UC Davis, at what was then New York’s International Wine Center. My success in high school chemistry further bolstered my confidence, and I decided to enroll at UC Davis to earn a degree in enology.

Unlike my undergraduate days, my time at UC Davis was spent as a very serious student. Although the crunch of studying and test taking took its toll, the novelty of learning about wine never wore off. To get practical winemaking experience, enology students work the harvest—at a time of year when winemakers work a minimum of l6 hours a day, six to seven days a week. Sleep, family and personal hygiene take a backseat to getting the grapes into the winery, crushing them and getting the fermentation process started.

Between my first and second years at Davis, I worked the l986 crush at what was then a little-known winery in the Russian River Valley. There was one factor that motivated me to go for the interview: Three years earlier a friend urged me to buy a $10 bottle of great Chardonnay—called Sonoma-Cutrer. Its remote location meant that there was less competition for the job, which was fortunate because I didn’t have any winemaking experience.

The following year I worked at Acacia Winery, which, unlike Sonoma-Cutrer, was an established winery that made its mark in the l970s by producing excellent Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. I had a car but no apartment and slept in a tent at a friend’s nearby vineyard. Once “accepted” by the guys at the winery, I was offered a bed in the tractor barn.

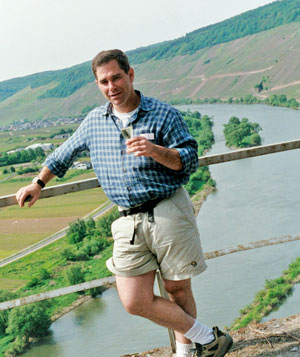

Although most Davis grads become winemakers, I decided to return to New York and put my background in sales and writing to use. After a few years selling wine to Manhattan restaurants and retail stores, I found myself in a unique position: I was sandwiched between the wine producer on one side and the consumer on the other, enabling me to observe which wines sold and why.

Was it quality or perceived quality based on reputation and marketing spin? By investigating answers to this question and others, my writing has been an ongoing education and a source of great satisfaction.

I was finally in command of my subject. I no longer needed index cards for direction. It was no longer a hard sell. I knew exactly what I was talking about, and I believed in what I was doing. On Wall Street, I was exposed to different groups of people—some had a sincere interest in helping their clients invest wisely; others were interested in success measured strictly in dollars. Yet, I found that winemakers’ egos were satisfied far less by profit than by striving to produce great wine.

Occasionally, when I’m running or driving long distances, I ask myself how my life would be different had I stuck it out on Wall Street. I know that I wouldn’t have been doing something I loved, where business and pleasure overlap on a daily basis. And you should see the work I bring home.