Cork has been the traditional stopper for 300 years and as such plays an important role in the ceremony of opening a bottle of wine as well being perceived as permitting wine to improve with age. A bad cork or one that has been infected by mold will ruin a bottle of wine. Winemakers are switching to synthetic alternatives because they feel cork “taint”—the wet basement aromas which a moldy cork imparts to the wine—is increasingly undermining the quality of their wine.

Twenty years after this defect was discovered, winemakers are frustrated that the cork industry has paid only lip service to the problem. With the development of synthetic alternatives some winemakers are changing. The most extreme countermeasure to date has been taken by an elite Napa Valley producer who recently bottled their reserve Cabernet Sauvignon costing $135 with a screw cap.

But cork producers claim they have developed a technique, which allows them to better screen for cork taint before the cork is put into the bottle. Winemakers say they have heard these promises before. Consumers—most of who are unaware of what cork taint is—do not mind synthetics. And most sommeliers embrace synthetics because they eliminate most of the problems with bad bottles. But all this applies to white wines meant for early consumption. Winemakers are cautious about tampering with tradition for their wines which benefit from bottle aging because is it not known whether a synthetic cork or a screw cap will permit a wine to improve in bottle like a natural cork is believed to.

The debate pits defenders of tradition who are sentimental towards cork such as David Noyes, winemaker at Kunde Estate. He states, “wine has a value that has nothing to do with its taste or flavor—it has a metaphysical value. Cork is a natural product and a traditional closure for wine. You are going to come across corked bottles from time to time—that’s just part of the mystery.” Against dispassionate, practical minded people who say to heck with tradition and aesthetics such as Christian Butzke former Professor of Enology at UC Davis, who comments, “The ceremony of extracting a cork is often really more a battle. I’ve seen experienced winemakers pour their own wine all over themselves trying to pull out a cork. The question is if people really want to maintain that ceremony or what I would say is to some degree an unknown adventure, both from a standpoint of getting the cork out and seeing if the wine is OK.”

This article will investigate questions which are important not only to winemakers but to consumers, collectors and sommeliers. What role does natural cork play in bottle aging and can it be duplicated with synthetic corks or screw caps? Should natural cork be considered sacred? How readily should tradition be abandoned when it gets in the way of quality?

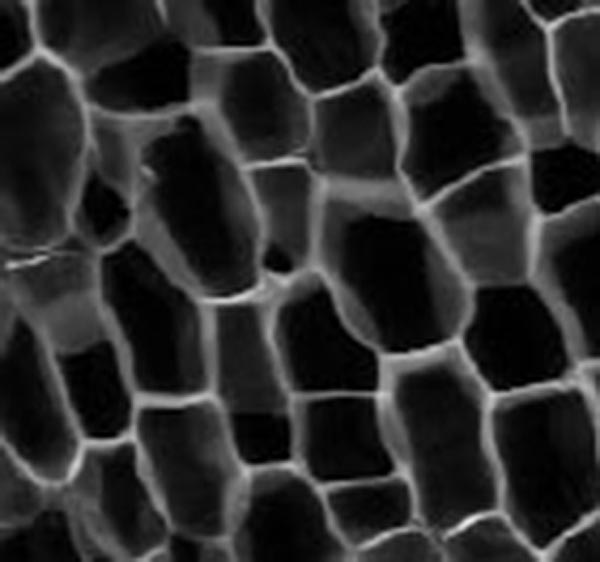

Cork comes from the bark of an evergreen oak, Quercus suber the majority of which grows in Portugal. After planting, it takes about 40 years to harvest the first commercially acceptable cork. Cork is composed of tiny air-containing cells. In fact, the cork is a time capsule of the air that was present during the eight years the bark took to grow back to the proper diameter to be harvested. The cell walls contain suberin, a waxy substance that makes cork water-resistant. Over half the volume of cork is empty space, which is why it floats in water and is easily compressible into the bottleneck. Natural cork’s flexibility allows it to conform to irregularities of the bottleneck.

The diameter of the cork is on average 24mm. The jaws of the corker compress the cork to16mm to fit it into the bottleneck. After insertion, the cork bounces back to 18mm—the diameter of the bottleneck— which means that 6mm or 25% of the cork is pushing out against the glass to create the seal. To improve the seal, the cork is coated with paraffin, which repels wine and Silicone, which acts as a lubricant to ease insertion and extraction.

A controversial question is what role does the cork play during bottle aging? Specifically, does air get through the cork and into the wine during aging? Vernon Singleton, UC Davis Professor Emeritus and an expert on wine aging, answers, “A qualified no. Dry cork is fairly permeable to oxygen. But a tightly fitting cork kept wet on the wine end is very slow to pass oxygen.” He adds that cork becomes a better barrier to oxygen - not a better seal - as the last few millimeters become saturated with wine. As oxygen gets from the outside to the inside it doesn’t jump straight into the wine but reacts with the wine that has soaked into the cork.

Singleton believes that air does get into the wine as an indirect result of wine evaporating through the cork. He states, “Water and ethanol are both small, volatile molecules and very slowly evaporate through the cork which accounts for the increased headspace in very old bottles. Since the cork is not pulled in, the headspace must be relieved by an inflow of air.”

James Herwatt, Vice President and General Manager of Cork Supply USA, Inc. in Benicia, California concurs that there is some very minor oxygen exchange between the cork and the wine which is believed to help the wine age. He adds, “But that’s an ongoing debate. People say that the cork breathes which is really a myth - the cork is not supposed to breath. Ideally, it is not supposed to allow any oxygen to get into the wine.”

Since aesthetics play an important role in the enjoyment of wine, one does not want to pull out a short, pockmarked cork from an expensive bottle of wine. Anna Matzinger, Assistant Winemaker at Archery Summit in Oregon explains, “We use a 1-inch cork for our white wine and a 2-inch cork for our more expensive wines. It’s an aesthetic decision but also a two-inch cork is for wines that have longer aging potential.” The pressure the cork puts against the glass is the important factor in preventing leaks. While a short cork can put sufficient pressure against the bottleneck, a longer cork gives somewhat better protection from leaks that are due to imperfections in the cork or the bottleneck. With a longer cork it is the less likely the wine will find its way all the way through. Whenever wine leaks out, air goes in to replace it and the wine ages more rapidly.

In reality, air does get into the wine either during bottling and/or through the cork during bottle aging. Evidence for this is the commonly held belief that half bottles age more rapidly than full bottles, since a given inflow of air would have twice the impact on a half bottle. In addition, mistakes during the bottling process can be responsible for leaks and premature aging. For example, after the bottle is filled with wine, a modern corker will pull a vacuum in the bottleneck, which removes oxygen from the headspace as well as preventing the headspace from being pressurized when the cork is inserted. With an insufficient vacuum, inserting a cork compresses that chamber of air so that with the bottle on its side or upside down, wine is forced to leak out between the glass and cork. Too strong a vacuum on the other hand, removes the oxygen but creates a negative pressure in that headspace which will be equalized by pulling air in alongside the cork. Either way, the seal is compromised and the wine suffers.

One cork supplier commented that winemakers pay less attention to bottling than winemaking, “We’re finding that winery owners will spend a tremendous amount of money on vineyards, a winery, machines, corkers, but they don’t check to see if they have developed head pressure in the bottle. They will look at the vacuum pump to see if it’s pulling a vacuum and if that gauge is moving they assume it’s pulling a vacuum but the lines could be stopped up with dust and it was not actually pulling a vacuum.”

In addition to an improper vacuum, overfilling the bottle can cause wine to leak beyond the cork. During bottling, winemakers leave a headspace between the cork and the wine to allow for the wine to expand if its temperature increases after it has left the winery. If the fill level is too high then the headspace will be too small to accommodate even a minor increase in temperature and will cause a leak. When the wine cools back down the volume contracts. Since the cork is not sucked in, air is “inhaled” into the headspace.

The most important issue facing the cork industry and winemakers is cork taint. Pulling a cork out of a bottle is an important part of the ritual and romance of wine. But this turns ugly - in direct proportion to the price of the wine - when the cork has become infected by a mold by-product called 2,4,6 trichloroanisole (TCA). TCA masks a wine’s fruit character with what is described as moldy, earthy or “wet basement” aromas. The incidence of corked wines may be no greater today than it was ten or twenty years ago but there is more attention being paid to this problem today. As wine prices increase, the concerns are magnified. Somewhere in the process – from stripping the bark off a cork oak tree in Portugal to storage in the winery prior to bottling – cork can become tainted.

Daryl Eklund is General Manager of Amorim Cork America in Napa sees wineries paying more attention to cork. He states, “As well they should—it is a wine contact surface. Winemakers pay a lot of attention to the inside of the press, the cleanliness of the tanks, barrels, hoses—anything that comes in contact with wine. Cork is the final contact surface. When the corks come in, you should do the quality control work you do with any other wine contact surface. Wineries doing that are having very good results and going ahead with natural cork.”

David Forsythe, winemaker for Hogue Cellars in Washington State has gone from natural cork to synthetic, back to natural and back to synthetic again. He comments, “This is still such a hot potato. To use natural cork we have to accept 1–1.5% of our corks having TCA. Realistically, it’s closer to 3–5%.” Forsythe believes that despite the quality control work he does 24-hour soak tests with 20 people smelling cork every day—he’s only catching part of the tainted corks; that more TCA is leached out after the wine is bottled and the corks soak for a couple of months.

As Forsythe points out, the exact percentage of bad corks is hard to pinpoint. The term itself—corky—is imprecise. The adjectives used to describe corkiness can also describe other wine defects, making TCA a scapegoat for other problems, such as an unsanitary winery. Tasters accustomed to the ripe fruit flavors of wines from California, Chile and Australia may call a wine with a microbial whiff, corked.

The human nose is able to detect TCA at an astoundingly low 2–4 parts per trillion, making TCA one million times more potent than aromas such as citrus, herbal or mint. To make matters worse, there is huge variation in individual sensitivity to TCA meaning tasters encountering a corked wine do not always agree. It can be detected at only 2ppt by some individuals while others do not smell it at 50ppt. Even for professionals and experienced tasters, it takes practice to learn to recognize corkiness—that’s when it’s obvious. The most insidious problem is when the taint is not obvious and the wine seems “off.” Winemakers worry that they risk losing customers because the average wine consumer—having no chance of recognizing cork taint—will taste a corked wine and whether it cost $10 or $100, not buy that brand again.

Another difficulty is determining exactly where the cork taint originated since it can occur anywhere between the time it’s taken off the tree to when it’s stored at the winery prior to bottling. Eklund states that one of the problems of the cork industry has been accountability—an inability to trace wood from where it was harvested to where it got to the market place. He explains, “A farmer would harvest it and sell it to a prepardore who would boil it and sell it to a mom and pop company who would punch it and sell to several different factories. A broker would buy from several different factories and ship to America through an agent who would sell to the cork companies. A problem in any one of those links—exposure to moisture, bad storage or sanitation conditions, poor boiling conditions - could result in a problem going into the bottle.”

Cork suppliers say that with the quality assurance they are doing, cork taint is affecting between 1-2% (a bottle in every 16 cases) of the corks they are selling. Anecdotal estimates from winemakers and sommeliers show the incidence is greater. Chris Howell, winemaker at Cain states, “You hear numbers like 1%, 1.5%, 3%, 5%. On average, it is certainly not more than that. But what happens to me is that I see some lots are worse than others and we don’t always catch them and that really bothers me. The cork supplier doesn’t catch them either because they don’t have a system in place to do it.”

Cork suppliers cite a newly developed analytical technique, which will vastly improve their ability to screen for bad corks before they get into the bottle. Solid phase micro extraction machine (SPME) has the sensitivity to pick up TCA down to 1ppt.

The Cork Quality Council, made up of Scott Labs, Amorim and Cork Supply USA, has purchased a machine which they share. Bob Fithian of Scott Labs comments, “It’s very good news for the winemaker and the consumer but it’s bad news for us because it’s sometimes difficult to buy cork that pass our standards. It’s not the final answer, it’s a tool to help us control our future.” Prior to this technology, screening was done by soaking corks in white wine in baby food jars for 24 hours. The wine was poured off and a panel smelled each for corkiness. Eklund states the drawbacks, “In addition to being time consuming and expensive, you’d be amazed at the level of variation of the human nose based on stress level, coffee intake, etc. We see SPME as an opportunity to crosscheck the human nose. It’s meant we’ve rejected more lots of cork.”

In spite of the cork company’s improved screening techniques and genuine effort to defeat TCA, many winemakers remain skeptical. Forsythe maintains, “The companies are based in Portugal and they own the forests and the plants – it’s the fox watching the hen house.” Some winemakers contend that there has been no improvement since TCA was identified twenty years ago. And because of natural cork’s monopoly, there appears to have been little driving force for change. But the development of synthetic alternatives represented a chance for someone to take market share. The market for synthetic corks is in the 10% range and growing which has gotten the attention of the producers in Portugal to address the problems: the way the wood is harvested, brought in from the forest, boiled and inspected prior to processing.

Noyes recognizes the benefits of synthetic, “From a technician’s point of view, synthetic cork is absolutely the way to go. It’s uniform, dependable and it doesn’t taint the wine and going to synthetic corks would save us $100,000.” But he sees a trade off he is not willing to accept, “Cork is a natural product and a traditional closure for wine. The Kunde’s are a traditional grape-growing family and have been here for 100 years—we’re very careful about the idea of introducing something synthetic.” Hogue’s Forsythe is less sentimental towards natural cork, “There were times when we stuck our head in the sand because everybody had the same problem—we’re all equally handicapped. But we see buying a different closure as an opportunity to increase the quality of our wines by 5%—a no-brainer if you can come up with the closure.”

An advantage synthetic cork has over natural cork relates to how it behaves under adverse conditions. A natural cork will leak before it will push and a synthetic will push but all the time it’s pushing it’s still protecting the wine because it’s not allowing oxygen to come into the headspace. When the wine contracts it will suck the synthetic cork in again. When wine is pushed beyond a natural cork (due to heat), when it cools back down, it will inhale and pull oxygen back in to replace it.

Synthetic corks can be advantageous for wines consumed within a year or two. Winemakers report that wines with synthetic corks tend to be tighter, more reduced and a bit more closed. But over the course of 8-10 months in the bottle, they shift from a preference for natural cork to synthetic, which keeps the wine fresher. For red wines which benefit from bottle age, however, few winemakers are experimenting with synthetic corks. The assumption is that because they form a hermetic seal, synthetic corks will function very differently from natural cork during long-term aging. Forsythe feels that using synthetic cork for red wines may necessitate changes in winemaking. He makes the analogy between barrel aging and bottle aging referring to the oxygen that the wine picks up in a barrel is very important to the aging process. “I think that process continues to go on in the bottle albeit at a much slower rate. One needs to look at one’s winemaking practices if you’re going to use a synthetic cork or a closure that doesn’t let oxygen in. Do I give my wines more oxygen? Do I age them longer before they go in the bottle?”

At least synthetic corks look like natural corks, especially Altech corks which is a chopped up cork and glue composite. Screw caps on the other hand, are the first thing beginning wine drinkers move on from and would seem to be an unlikely choice for expensive, long-aging reds. Nonetheless, Plumpjack, a 10,000 case Napa winery producing mostly ultra-premium Cabernet Sauvignon, defied this logic and bottled half (300 cases) of its 1997 Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon with screw caps.

The announcement was made during the Napa Valley Wine Auction leading some to believe it was a publicity ploy. With neighbors like Dalle Valle, Screaming Eagle and Harlan, attempting to generate some publicity would be understandable but John Conover, General Manager of Plumpjack notes, “We didn’t have to do this, I don’t need more publicity. We sell out every year and have a waiting list for people to get our wines.” Between the cost of a custom bottle and a minimum purchase of 56,000 screw caps—fifteen times what was needed—the project cost over $100,000. “People have been talking about it for the last 18 years and no one wanted to be the first. There are two other producers I know of that are coming to market in the next six months with screw caps,” Conover adds.

Plumpjack’s move received a lot of attention and raises questions not only about the future of closures for age-worthy reds but about the extent that one producer and ultimately others may go to register their displeasure toward natural cork. One of the investors in the winery - Gordon Getty of Getty Oil—also owns three restaurants, an inn, a wine shop with another restaurant and wine shop soon to open in San Francisco. Conover says, “Because we have these outlets, we’re seeing a number of things happening—one of which is a greater percentage of bottles being sent back because of TCA. Two people would drink let’s say 1/3 of the bottle and leave the restaurant. The sommelier would taste the wine after they’d left and found that it was corked. Hopefully, the consumers were not turned off to wine or to this specific producer or were not thinking that we had stored the wine incorrectly. We considered these factors and decided that screw cap was the way to go.” Plumpjack hasn’t abandoned corks altogether, they still bottle 95% of their wines with corks but they think that that the screw cap is the future. They will bottle the ’98 Reserve in April with the same 50% in screw cap and have asked UC Davis’ Dr. Christian Butzke to conduct an annual independent study to find out is whether a screw cap will permit a wine to improve during bottle aging like a natural cork is believed to.

Plumpjack’s metal screw cap is a barrier which air cannot diffuse across. Therefore, aging reactions which are not dependent on oxygen—white wines turning brown, reds taking on a more brickish appearance and oxidation of phenolic components making the wine smoother—will not occur. But this does not mean a screw cap will “freeze” a wine in place. According to Singleton, the chemical reactions responsible for bottle aging are not dependent on oxygen, implying that both a screw cap (and a synthetic cork) will not interfere with bottle aging. “My opinion is that bottle aging doesn’t occur unless there is a considerable protection from oxygen. So rather than saying slow contact is desirable, I believe that slow contact may not be desirable,” Singleton says.

Conover feels that the slight differences between cork and screw cap will be detectable for those with professional palates, but he doesn’t think the average consumer could discern the difference. He cites an added benefit, “For the collectors, this is a positive - they’d love the wines to age longer and eliminate what I think is a minimum of 10% TCA.”

Plumpjack had to consider the marketing ramifications because screw caps could cheapen Plumpjack’s image. It would be far more difficult for a larger producer who relies heavily on marketing and working through the three-tier system. For example, within weeks after Plumpjack announced bottling 300 cases with a screw top closure, Sutter Home in a less publicized move, switched from screw caps to natural corks for their 1.5L bottles —about 24 million corks. Sutter Home’s marketing department was banking on the fact that the cork finish would elevate its image making it easier for its sales staff and wholesaler to sell the wine.

A more subtle reason winemakers are hesitant to replace cork is due to the association between expensive wine and natural cork or jug wine and screw cap. In addition to a wine’s sensory factors such as color and bouquet, the brain also processes non-sensory information. The type of closure will activate stored or cognitive information which is very powerful in determining liking and explains why the same wine tastes better on a Tuscan hillside or out of fine glassware or with delicious food than out of a thick-rimmed bar glass or less appealing surroundings. While Plumpjack’s frustration with cork is understandable, are they underestimating the cognitive effects of a screw cap?

Conover admits that the screw cap takes some of the romance away but Plumpjack’s thinking is that the type of customer that purchases its wine has had experiences with cork taint, knows how to identify it and knows that it’s a problem. He comments, “Someone with less experience views this as a cost saving measure. We found that the more knowledgeable the consumer, the better they understand why we did it. I can assure them that they won’t have a cork tainted bottle.”

“It’s a good closure, it’s fun to talk about but I don’t think it’s going to be a major closure, Herwatt states. He adds, “The average wine consumer doesn’t perceive taint as a major issue with cork. The biggest concern with cork for most people is getting the cork out without breaking it and resealing the bottle.” Eklund comments, “Screw caps are not without their problems if you talk to the people that use them. With a temperature change, the metal will expand but the glass is inert. It’s not a perfect system but if done right, screw caps can be a viable alternative, even if the aesthetics are not appealing. There is a part of the American soul that wants something traditional - that associates romance with pulling a cork.”

The problem with discussing the relative merits of alternative closures is that in spite of natural cork’s longevity, its effects have not been studied. Butzke feels that a lot of assumptions have been made about cork as a closure including the breathing. He says, “As with so many things about cork, people have opinions and imagine how things work but there is no research.” Butzke claims that because of the inherent variability of a natural product like cork, nobody can accurately predict how a wine is going to age. He adds, “Just as with any piece of wood, there will be natural difference between individual corks. With a wide range in the amount of oxygen that comes through the cork into the wine—what is called random oxygen—some bottles turn brown more quickly than others. Which makes it difficult to predict that all twelve bottles in a case of wine will age the same—it’s likely that they won’t.”

Aesthetics do matter; any wine lover who enjoys admiring the cork after removing it from the bottle will agree. And there is also something comforting about a natural product like wine being stoppered with a piece of tree bark. Is eliminating cork taint worth diminishing the aesthetics of wine? Yes, for inexpensive wines. The uncertainty is at the high end, where natural cork plays a more important aesthetic role. The resistance to change at the high is two fold: one is the fear that no one producer wants to break rank and be the first to do it. Secondly, until there is more data on how synthetics and screw caps perform, there will be reluctance among collectors to invest in wines without natural cork. Alternative closures will become more common according to how reliably the cork industry can produce a taint-free product. Only time—in the bottle—will tell.

—By Jordan Ross, Global Vintage Quarterly Web Site, Jan-March, 2002